This thesis is an archive of family history, memories, materials, and projects that document and reflect on lives and legacies within diaspora and displacement.

Table of Contents

- Beginnings

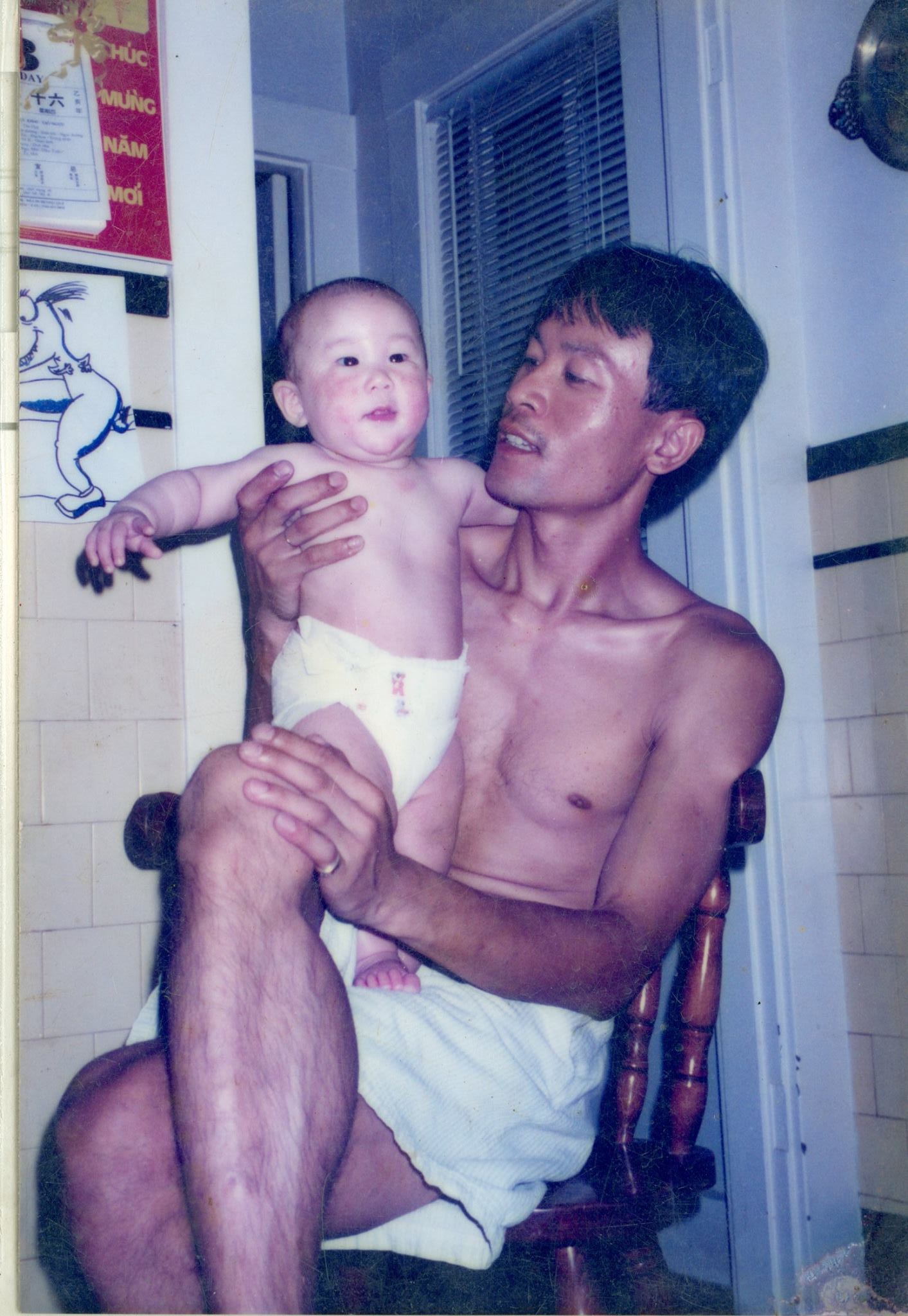

- Ba

- Ma

- Home

- Epigenetics

- All immigrants are artists

- Cutting my teeth on

- Betting on losing dogs

- Fragments

- A love letter

I.

Beginnings

A long shot | ˈā ˈlȯŋ-ˌshät |

noun

1: a venture involving great risk but promising a great reward if successful

2: an entry (as in a horse race) given little chance of winning *

This thesis attempts to archive my parents’ displacement as Vietnamese refugees and the new lives they built in America, lives rooted in fracture and evidenced in incompleteness. By taking stock of these fragments—in memories, reflections, and materials—this document seeks to challenge the dominant narrative of refugee as agentless victim by highlighting the creativity, resourcefulness, and resilience of displaced persons, and the legacies they bring into this space.

Drawing on family history and lived experiences, my work contends with home and belonging, displacement and intimacy, and lives measured in invisibility. I look for transient and unstable mediums—seeds from my mother’s garden, sharp edges of glass, your eyes locking mine from across the room—and ask them to translate for me these stories, these sentiments. In documenting my parents, I begin to document myself, breathing reason and weight into the fixations I fall asleep to and the body I wake up in.

After their separate escapes and respective journeys to America, my parents met in 1979 in Boston, Massachusetts, half a world away from a crumbling motherland, and together built a home from nothing. I was raised in this mythology of a mother and father who fought off sea monsters and pirates, rode waves as tall as mountains, cheated death too many times to count, and still lived to tell the tale.

My parents have measured their success in the quality of life they could provide their daughters, giving up everything they had, gambling their own lives, to afford us ours. They gave me the luxury not only to dream, but to pursue these dreams.

A long shot.